Paying for Recipes Reaffirms Their Value

A brief reminder that recipes are products of culture, art, people’s labor, and expertise!

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s only $30 a year. That’s like one shitty cookbook! Upon becoming a paid subscriber you will receive a copy of my digital Burnt Basque Cheesecake Cookbook Zine! Your funds will also go towards future zine publications as well as making sure that the vast majority of content is free for all.

No one wants to pay for recipes. Is a sentiment I hear over and over again from recipe developers, cookbook authors, food writers, and food adjacent professionals.

The most common comment on a cooking or baking TikTok or reel is Recipe? Recipe please? Where is the recipe? Can I have the recipe? I’m gonna go out on a limb and guess that the most common DM food folks get is “recipe?”

The viewer expects (and often demands) a recipe to accompany every single food video or photograph they see on social media. An expectation that no doubt has its roots in food blogging, early cooking/baking YouTube videos, and Instagram posts.

The audiences’ hunger for recipes is insatiable. It honestly brings out something dark or at times silly in people. People even get angry, cranky, aggressive, and sometimes straight-up offensive. I even had some people DM some pretty horrible things when I told them I don’t share certain recipes for free. I will spare you the details of the nasty messages but the takeaway here is that folks have a tendency to become emotionally dysregulated when they don’t get a recipe they feel entitled to for free.

So how do we reconcile this tension between the public who feels entitled to endless free recipes and recipes as labor and an art form?

We talk about it, endlessly and passionately! And by reminding our audiences what recipes really are—products of culture, people’s labor, and expertise!

One of the main reasons why I think people need to charge for their recipes is because it challenges the preconceived notion that recipes, unlike other forms of culture and art, are meant to be free for one reason or another which inevitable boils down to devaluing someone’s labor and knowledges, as well as aiding in erasing their artistic, cultural, and historical value.

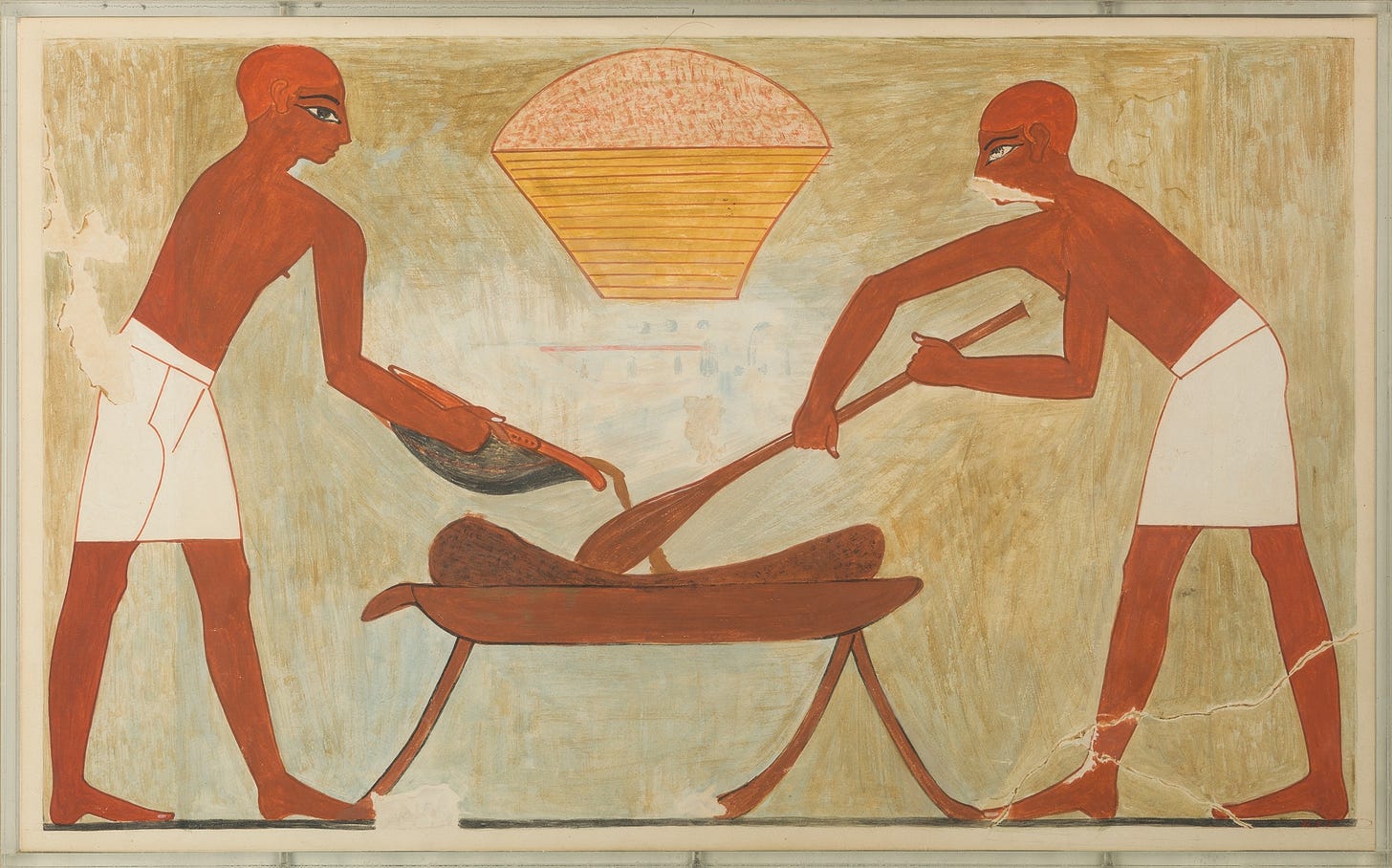

Since recipes are cultural artifacts which are often preserved through oral traditions and histories, they get excluded from the culture economy even though other forms of ephemeral art and culture are not. Museums buy paintings, vases, statues, books, etc. And certainly some of those may depict or contain recipes—and yes the subject, theme or focus of a collection might be, when it boils down to it, recipes if that is the mission of the curator. But I want to talk about the idea of a recipe as an object because a recipe, decoded and analyzed, contains so much about culture.

If we pay for some cultural objects but not others, what does that say about our society? Do we value certain types of knowledges over others? Yes, there are many hierarchies of knowledge. Quantitative data is more valuable than qualitative, I think that’s slowly changing. A lot more research funding goes to quantitative research than qualitative research which is predominantly done by scholars who come from diverse ethnic, racial, gender, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Yes, even knowledge is colonized.

VALUES OF RECIPES

I often write and talk about recipes as objects of cultural heritage. Recipes allow us to preserve the cooking and baking traditions of people across space and time. We can learn so much about the culinary practices of our past through the study of cookbooks and the recipes they hold.

Alicia Kennedy in a recent essay, “Recipe as Object,” discusses the value and role of recipes.

“That overproduction of everything is the norm, and recipes—an age-old form used for the transfer of heritage and skill dating back to at least Babylonian clay tablets from 1700 BCE—have become objects unto themselves, something paid for that either becomes absorbed and taken throughout life, shared and cooked repeatedly, or is easily discarded for the next.”

Recipes, similar to furniture/ceramics (I guess pick any artifact), need to be researched, developed, designed, fine-tuned, written down (recorded in some way), and disseminated (distributed). In most systems, all of these steps are considered labor. I mean it really is a lot of work, and it is a lot more work to do it right.

There is also material cost to consider—in the production, recording, and sharing. You need ingredients to experiment, test, and video/photograph (record) the recipe. And we should also mention all the non-food related labor. Sure, yes, I am a cook and baker. But I am also a historian. I am also a writer and editor. I am also a videographer and video director and a sound technician or engineer and maybe a publicist or marketing and art director. I have lost track of all of the things I need to be if I don’t have help or hire someone.

Maybe the best approach for easing the tension is by reminding the public and our individual audiences that recipes are a product of culture and people’s labor, expertise, lived experience, culinary training, intergenerational knowledge, and more.

And often paying for something is a good idea, especially if you’re paying a person. Paying for something creates a contract of accountability. You pay someone for something and you have an expectation. If that expectation is met or exceeded, you’ll likely pay for more products from that source.

As trust in food media companies continues to dwindle, the public relies more on independent food writers and recipe developers for recipes (and content creators of course). That’s why we all have a responsibility to talk about our work as work.

Also, there are instances where paying for the recipe means being a patron of a food writer, an artist who writes evocative, creative, and beautiful recipes. There is literary value in these types of recipes. It is the prose and the poetry of food we pay for. Recipes are not limited to being didactic. They are writing. They are video. They are photographs. They are art. All of these forms have the ability to emotionally move us like any work of art. I really want to write about recipes as art in much more detail, more to come, promise!

The public’s demand for free recipes needs to be checked. And this can only happen if we talk more openly about the work/labor and the creative and cultural value of recipes—continue to acknowledge and recognize recipes as intangible artifacts of cultural heritage.

CONTINUE TO BE CONSCIENTIOUS CONSUMERS

We can also apply the same strategies we use as ethical and conscientious consumers to purchasing recipes. What you really need, and this is where it is super helpful to think of recipes as products in their own right, is to do a little research to evaluate whether paying for the recipe is a worthy purchase like any of your other purchases.

Also, if a recipe is free, ask yourself, why and how is it free? Is anything ever really free in the attention economy we live in? How much will it cost you in time and ingredient cost? Don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of good reasons why people decide to share recipes. I will discuss my reasons for keeping the majority of my recipes free further down.

I understand why most food bloggers (and now content creators) don’t charge for their recipes, it’s because they don’t rely on the recipes themselves for income (and most food bloggers do come from a higher socioeconomic background but that’s a different topic for a different day). Ultimately, these individuals are bloggers not recipe developers or food writers. Their money comes from advertising be it ads, collaborations, affiliate links, and so on. I, and many others, really do not want to be that.

If a recipe is being sold, I would ask myself, what makes it a product worth buying? You can buy it to support the person you follow (having the bills paid so that a person can spend time and resources on research and development is critical) or you can buy it because you recognize one of the values we discussed earlier in the recipe itself.

Am I saying that all free recipes are shit? No. But, would I be more wary of a free recipe especially for something that requires quite a bit of knowledge or expertise? Definitely. I’m not necessarily including food media publications here. Although, the recipe testing and development process at some of those is, how do I put it mildly, questionable. An editor can only produce, edit, assign so many recipes a week, a month, a year. Magazines usually have a very limited budget for recipe testing. You should definitely periodically re-evaluate what food media publications you support be it monetarily or with your attention cash.

REASONS THE MAJORITY OF MY RECIPES ARE FREE:

First of all, I do sell some of my recipes—specifically those that I developed for my micro-bakery. These recipes took years to perfect. A lot of hours, a lot of failure, a lot of experimentation, a lot of energy. And I want to keep doing that, so some important recipes have been neatly packaged for your consumption.

But here are my current reasons for not charging for the majority of my recipes.

First of all, I don’t rely on recipe development as my main source of income. Recipe development is something I do on a case by case basis nowadays.

Additionally, my recipes are free because I want as many people as possible to learn about Ukrainian culinary culture and engage with Ukrainian recipes, especially now when Ukraine’s culture is once again under threat.

I also love the act of sharing my favorite recipes that I tested, modified, or adapted and not necessarily developed. I also like to write recipes in my own words, in my voice, and through my thought process/mindset. It’s great writing practice. Give it a try. Seriously! Try writing about the art (process) of making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

For me, at the end of the day, free and open access are part of my ethos. I hope to one day create an extensive archive of thoroughly researched, tested, well written, and beautiful recipes. Recipes that hold artistic, culinary, cultural, and historical value on and off page.

ADDENDUM

Historical recipes are an interesting beast. On the one hand, most historical recipes are in the public domain. You can go online, go to the Library of Congress, and find some super old cookbooks and cook your heart out.

But not all historical essays can be accessed with such ease. Some recipes need to be found in archives, translated, and adapted to modern ingredients and kitchens. And those historical recipes often require translation which is an entire other field of study—fields of study. Not just translating from a different language but from a different time as well. Old nomenclature for flora and fauna, old names for preparation and units of measure, as well as understanding the science and relationships of materials in the cooking and prep.

Some recipes only exist in the minds of a few people. We have to track down those folks, interview them, transcribe the interview, fact-check, test, and adapt the recipe for home-cooks. Not so easy. Are the majority of food bloggers in the business of doing this type of work? No. But those who are are often grouped or overshadowed. I like to think of myself as a recipe detective personally!

Purchasing a recipe from a reputable source often means the recipe has a higher probability of coming out well if not on the first try but the first couple tries, which will save you money, cut down on food waste, and most important of all, save you your most precious commodity, time.

The likelihood of you successfully learning how to make a dish increases exponentially if you do a little research in the beginning and decide to learn from food people who are ethical, knowledgeable, and passionate about their craft.

MORE OF MY EVER-CHANGING THOUGHTS ON THIS TOPIC TO COME!

This is so good!!!

I will be featuring this in my next newsletter because I think it’s important for people to refer to this. Cooking is not just an art, people who cook are scientists, mathematicians etc. As poetic cooking can be, there’s a moment of erosion on one’s spirit sometimes cooking and it failing when it comes to testing for the third or fourth even sixth time. Not from just from “failure” but the financial cost of it all is immense.

I used to work in a kitchen. But since I started writing I’ve opted not to develop recipes because I don’t have the emotional nor financial bandwidth for them.

Gonna restack this forever and ever.