If you’re enjoying this newsletter, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s only $24 a year and you get a complimentary copy of my BURNT BASQUE CHEESECAKE RECIPE ZINE.

Let’s start by clearing the air. I’m the last person who should be writing this, but I guess I’m better than no one. My hope is for someone more important than myself—more established in these industries—because this rant needs to be taken seriously and I hope it inspires traditionally published authors and tenure processors to speak up. Don’t get me wrong, I have years (decades) of experience in these industries, but I’m straight up a nobody. I have been on enough sides of these careers to see how the sausage is made but I also recognize my own privilege in being able to write this opinion piece from an “easier” place because I don’t have much directly invested in these industries. On the other hand, as a new writer and as someone who does want to write full time, I am scared that being blunt in this piece might burn some bridges or hurt my chances of achieving my own writing goals. There are some bridges I’m not at all interested in crossing. Bridges that are one bad day away from collapsing. As you continue to read this you will see that there are definitely bridges that I refuse to cross and this is what today’s essay is really about. But seriously, who else is going to write about it though?

*This essay is for both established and new writers with a different message for each group.*

Some of you are already familiar with my work, you know that being critical of broken and exploitative systems, specifically publishing, academia, museums, cultural institutions, art world, media, and higher education is an important driving force of my writing. Furthermore, my work is motivated by advocacy for fair wages and equity in these spaces.

I recently read Summer Brennan’s piece Writing A Book is Like Going to Grad School: Two goals that come wrapped in poverty, personal fulfillment, and professional gain published a couple weeks ago and I, actually WE collectively, need to talk about it. How can we not? I’m so tired of seeing traditionally published authors write stories that explain away instead of offering criticism and calling for active change of broken institutions. Isn’t it obvious that stories defending traditional publishing and academia perpetuate and in turn allow these systems to continue to take advantage of artists/staff/writers/editors etc. Those of us in the arts and humanities are in dire need of transparency and it begins with acknowledging the realities—not just describing the idealized goals and romantic ideas. There’s nothing romantic about suffering and no one earns anything from it other than, well, suffering.

I know calling people out is—how do I put this mildly—not a popular practice in writing/art communities and academia because these industries are so reliant on personal relationships. Boo hoo, we share ideas and aren’t we all a little bit better for presenting those ideas for scrutiny? Did we forget the ethos of peer review? We can dissect ideas without getting personal. Our communities are very small and people feel pressured to be nice to one another and apparently the only acceptable form of niceness is staying quiet and not criticizing individual authors or the system they participate and actively defend, not challenging ideas that are repeated and paraded. On occasion I have been told to shut the fuck up, and sometimes they’ve been right or at least should’ve been right. Too often, I think, we worry that we’re just the insane person on social media—the weird family member who isn't invited to all the holidays. Ultimately we hold ourselves accountable, we decide on the decorum and the level of discourse. And we must necessarily talk about things that are taboo, impolite, uncomfortable, or otherwise going to upset some people. So let’s have at it…

I am going to say what a lot of us are thinking, but are too afraid to say to one another. Writers need to stop defending broken systems. PERIOD. Wasn’t such a bad thing to say, right? Pretty obvious, but there’s more…

Reading Summer’s essay (which I will use as a case study to talk about these larger systemic issues; my respectful apologies for the target practice) was especially worrying because it drew parallels between two highly exploitative institutions that are in dire need of systemic change. It is my belief that every writer, artist, professor etc. who has succeeded in these traditional spaces has a responsibility of holding these institutions accountable and improving them. This begins with transparency—and that’s a hell of a difficult thing for a lot of people. It is why we have whistleblower protections, it is why NDAs were recently made defunct in many places, and it’s why we have any labor protections at all. In keeping institutions accountable, we can all begin here.

Unfortunately we continue to see the opposite, often (and I find ironically) on this very platform. A space that was born out of desire to challenge traditional systems. But for the majority of traditionally published writers on Substack they continue to perpetuate or run parallel to legacy media, academia, and traditional publishing. Let’s dive in and take a closer look at the themes and issues presented in Summer’s essay. Summer begins by writing (emphasis my own):

At that point, despite being armed with a book contract from a well-respected small publisher, I had only received a payment of $2,500 to write the book. That was after working on it for a few years already—enough to knock a decent nonfiction book proposal into shape…

Despite how it may sound, I am not in the least bit resentful or bitter about any of this. In fact, I count myself lucky.

It is so confusing to me that a successful writer could think it appropriate to write this last sentence (honestly this entire essay). Just because you get lucky in an industry it does not mean or prove that the system works. No. It just means the system worked out for you. You count yourself lucky.

What is the point of titling and framing this narrative about self imposed ascetic-like academic-induced poverty leading to personal fulfillment and career success? This whole sentiment and similarly written pieces are giving—the exploitation and abuse was totally justified because it gave me opportunities that worked out for me.

Summer continues to show the same framing about her experience in graduate school where she admits to being “extremely poor the whole time.” She writes (emphasis my own):

Even in the instances when someone actually pays you to do it (graduate school), you won’t make much, and most of the time it just costs a lot. But if you’re not unlucky, it does change your prospects, sometimes dramatically. It changes how the world sees you. You become qualified—or at the very least you will now be perceived as being more qualified—in ways that you weren’t before.”

Once gain, the author makes the case that suffering, living in poverty, being horribly underpaid, and let’s be honest straight up exploited is justified because there is a chance you will get lucky and your professional prospects will improve. Sure, the author asserts that the suffering somehow transmogrifies you into a better person or that some unseen, omnipresent They witnesses your suffering and so benevolently swoops down to miraculously lift you to your earned, exalted place at their table. Total Eyes Wide Shut, right? They wish. It’s a lot more tame and gross.

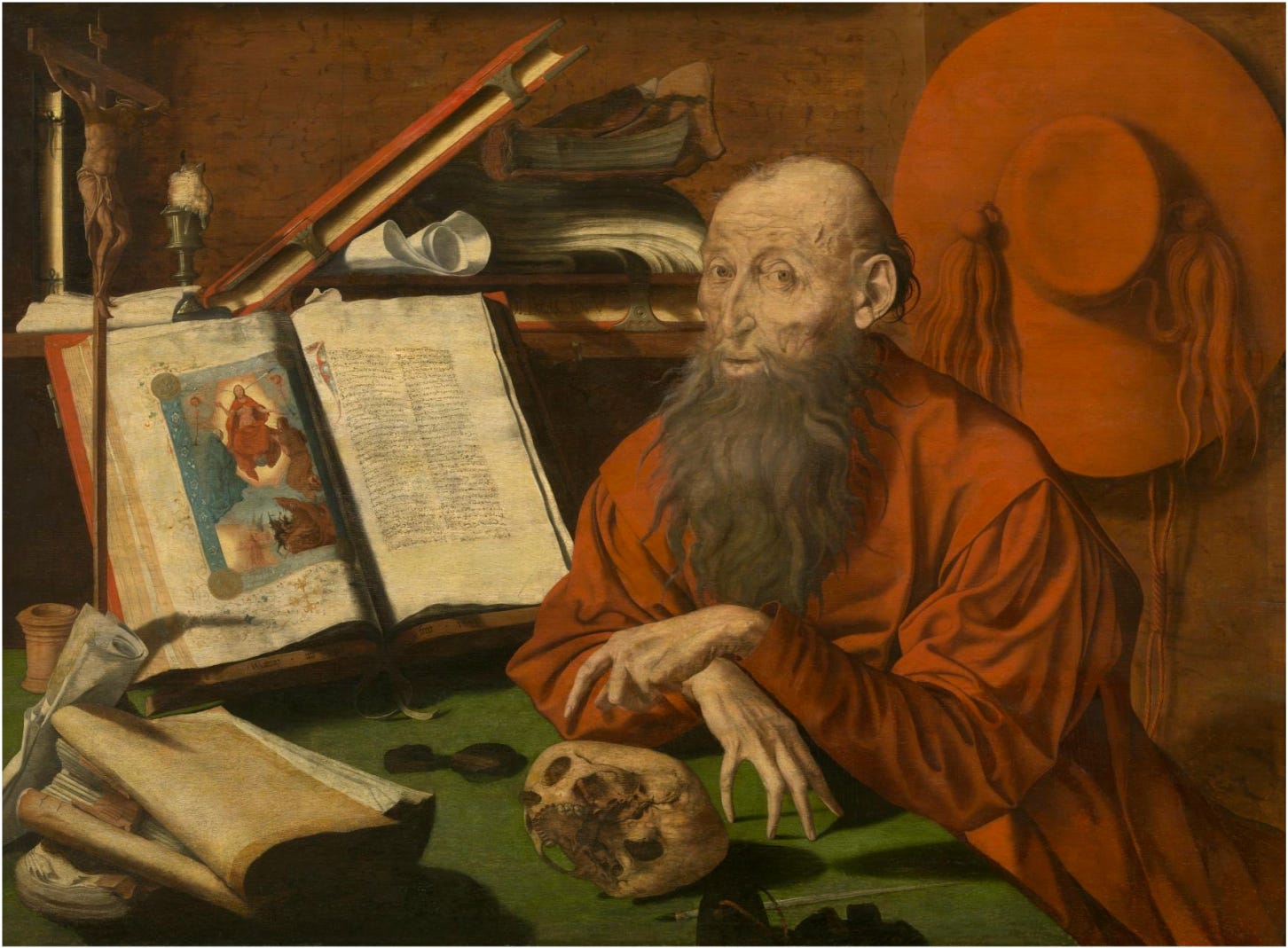

This is the same suffering artist trope that we have been seeing for centuries now. And look how much we splurge to devalue artists at every opportunity, with AI being the most recent example of someone who can’t make art trying to figure out how to remove the highly skilled and laboriously working artist from the equation of making art. Isn't it time to stop thinking about suffering as a rite of passage for writers/artists/academics? What the hell even is suffering when it’s such a lame and shallow attempt at imposing cruelty on someone? The only reason poverty and/or suffering exist is because of the systems in place. It is finally time to change not only the narrative of how we talk about writing but the systems within which writing operates.

I don’t mind suffering. I want my basic needs to be met and I want to live a fulfilling life so that I can give myself entirely to my study, my craft, my passion. Sweat and bleed like an athlete because this shit is labor, it is physical and it’s bullshit to set an economic bar. I’ll suffer through the hard work to reach my goals—the hard work shouldn’t be 1001 Instant Ramen Recipes and risking my physical and mental health.

Just so we are all on the same page. I don’t know Summer. I really don’t want to appear to be passing any personal judgment on them. I am reading what they wrote and I am responding to the writing voice of their essay. As someone who also writes, I would be mortified to be called out but I also try to approach these things with empathy towards a wide audience. And if what I am writing upsets anyone, I hope it upsets people who are doing these things that I feel are bad. Because anyone can change what they do.

Having said that, this next part of Summer’s essay is absolutely unhinged and goes as far as to blame new writers for having too grandiose of expectations from publishing. Don’t get me wrong, being realistic about how things are and how they really work is my cup of tea and I’ll sip that all day long. Being realistic is very important to demystify self destructive habits for first-gen authors. But it seems inappropriate to write about expectations of new writers when you are a seasoned and published writer who is discussing your own writing success story. Summer writes (emphasis my own):

“But I often see a fair amount of shock expressed on social media when people learn how much an author has been paid by their publisher. This is because most people still have an unrealistically rosy view of the experience…

They imagine quit-your-day-job advances, lavish parties, free boozy lunches, and all-expenses-paid book tours with suites booked in swanky hotels. A bouquet of flowers and a fruit basket will be waiting for you in the room.”

I do agree that a lot of new writers (including me) don’t have a clear sense of how much they should expect from their first advance in their specific field or genre of writing. But that’s because there is so little transparency from the industry and established writers on the topic of money. There is no database where new authors can go to look up averages for advances. It is information that you can try to gather through informational interviews and connections, but it’s not easy to talk to writers about money even in 2024.

There are of course exceptions and things are changing slowly for the better since traditionally published authors and folks in academia are becoming more transparent and honest about their experiences and pay. But we still have a long way to go as far as financial transparency goes in publishing. So it is not the fault of a misled new writer who is just starting but the systems that led them to believe that writing books can improve their quality of life and move them into a different social class. It is also okay to think of writing as a tool for social mobility. Because it is. Shouldn’t all labor be?

But let’s get back to my main point which is asking publishers to pay their writers (and staff) a living wage and universities to pay their graduate students (and staff this includes lectures and adjunct faculty) a living wage. This! This is the most common sentiment of most new authors that I know. The majority of us don’t want to be rich or have a fancy lifestyle, we just want to write, do research, and create.

This connection between traditional publishing and academia is even more sinister when we think about the long history of these two institutions. Why would a publisher need to pay a writer if the writer has a tenure appointment at Yale or Stanford? Why would universities need to worry about providing for their graduate students or publishers for their authors when they are independently wealthy? That’s pretty much who was able to access these spaces for the majority of their existence. And all those unpaid internships.

With adjunctification in academia running ramped nowadays and tenure jobs are fewer and fewer the connection between the two is even more appalling. So, of course, publishing is on board with letting their writers work multiple other jobs while working for them for pennies, same with universities. This is the definition of exploitation. Or at the very least we are watching the free fall devaluation of this labor. Summer concedes by saying, “Being a professional writer often means actually working in academia, too. Even many of the most commercially successful writers are also university professors and writing instructors. That’s just the way the system is built,” a sentiment that is just too common amongst published authors and tenure faculty. It is complicity and washing your hands of the stink doesn’t remove the giant turd in the room. Smearing yourself with it and joining the other stinkers isn’t that appetizing either, but hey at least you’re in their club now.

I want to remind my fellow writers and art/humanities professionals that systems are built and rebuilt and rebuilt over and over and over again. They are not stagnant as much as the people who have the most invested in them the way they are, want you to believe. Systems CAN and SHOULD change. This includes archaic institutions such as universities and publishing.

Sadly, it is usually the complete opposite. People who get through these systems successfully in turn protect those systems since now they have the most to lose or they would have to reconcile with the fact that they have been exploited for god knows how many years. To quote Janel Page from Dark Side of Reality TV on her experience on the show America’s Next Top Model “and people who succeed within flawed systems are the best people to perpetuate it.”

It is super clear from the way publishing and academia treats its workers (this includes authors) that they don’t care about providing for them or giving them a quality of life that doesn’t qualify you for food stamps. Summer writers:

“People get MFAs not just to become better writers, but so they can teach at a college and perhaps be given a small faculty cottage to live in that smells only slightly of mildew.”

That’s exactly it. You will continue to live a life of poverty probably in a mold infested house that most likely still has lead paint and you will start losing your brain cells and health because you want to better your career or finally be able to do what brings you an ounce of joy praying that you get lucky fast enough to not get cancer. Really a great set up for success with all that suffering. Or do we just want poverty-lite?

We are almost at the end, I promise. Towards the end of her essay Summer says the following (emphasis my own):

“The arts and humanities are not trades. They are not and never will be “big business” for the majority of their practitioners, even though big businesses are sometimes built around them. Yes, the competition is fierce, but in our modern economy and media landscape, it is easy to become confused about their value, or to denigrate those who toil away in their trenches.”

The arts and humanities are not trades? Frank Lloyd Wright might be a silly example for his, uh, ambitious engineering ideas, but he’s a household name for his art! Syd Mead —an artist known for designing the visuals of Blade Runner, Tron, Aliens, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and so so much more, graduated from ArtCenter College of Design and worked as an industrial designer at Ford before literally drawing our visions of multiple futures for decades to follow. Ansel Adams taught there. In World War II, ArtCenter ran a technical illustration program with the California Institute of Technology.

The arts and humanities are necessarily trades—they require deep technical knowledge and skills with entire industries depending upon the bodies and brains that do this work. Tools and knowing how to use them. Materials and knowing how to use them. It is a measurable, empirical and repeatable science lest we forget the dreaded time before computers when people in starch pressed shirts leaned over large tables with graphite and gum and straight edges. The arts and humanities are trades. PERIOD.

What is the value that the author is communicating in their essay? Because to me this whole piece reads like a defense testimony for an abusive spouse or a terrible boss. They and anyone who has written similar work obviously do not value the people who work in the arts and humanities, and the effort is to argue that this is just how things are. Fierce competition—but such a high demand for the arts and humanities! Modern economy and media landscape, oh yes let’s capitulate to an economy struggling to maintain labor rights and a media landscape runaway with Orwellian cries of fake news, truthiness and AI hocus pocus. To toil away in the trenches like your workplace, your career, and your work should be a goddamn war? I can’t roll my eyes hard enough. Someone else is getting rich off what we make. You think book binders are paid well? When the going gets tough, the lowest paid are the essential workers.

Pay people fairly. Don’t pay writers in rain checks! Don’t pay writers with hope! This is our version of being paid in exposure, fuck exposure. Don’t dangle the possibility of getting lucky and getting those doors to success and financial stability to finally open. I’ll go Vegas or invest in crypto if I want to gamble. Honestly none of this even matters what really matters is the fact that in 2024 we still as a society are completely okay with writers/artists/humanities grad students/editors/food journalist being exploited and fucked over by these self-serving institutions.

To be honest, reading the essay left me feeling dead inside because I know this is exactly what the large majority of successful published authors in traditional publishing believe. It is still pulling the ladder even if you’re looking over the edge and cheering for everyone down there. They believe and proclaim rather proudly that “That’s just the way the system is built.” They remind you that you should be focusing on the future and hope that this “little bit” of exploitation whether in graduate school or writing your first book is just a normal part of the process, an experience we all need to go through to get future opportunities to present themselves to us. Just keep trying, just keep underselling your work, and you might get lucky.

Luck is not equitable. Luck is designed to favor those in positions of privilege and power. Just promise me that you will remember this one thing from this essay. No promise of success justifies exploitation of people. No promise of opportunities, book deals, teaching gigs, is worth the price of human suffering. We can do better, together.

To be honest, most young writers are disillusioned with traditional publishing and prefer to do their work in small community-centric ways and through self-publishing. We are seeing this happen not only in publishing but in legacy media as well with the rise of independent media made possible through platforms such as this one.

Summer concludes their essay with the following paragraph:

“I laughed when that acquaintance asked if I was still living off the earnings from my first book, but the reality is that nine years after it came out, I am self employed as a full time writer, which wasn’t the case before. I write books, articles, and essays, teach workshops, and publish a newsletter for a living. Much of my life in the past decade has indeed been shaped by the fact that I published that first book all those years ago. In a way, I guess I am still living off that Oyster War money, after all.”

First of all, congrats to her as she kept pushing forward doing what she endeavored to do. That’s phenomenal. But I do want to point out that correlation is not causation. All the good things that came after the publication of her traditionally published book didn’t happen solely because of the fact that they became a traditionally published author or got their MFA. Summer’s ability to be a full time writer happened because of a thousand other factors the author didn’t disclose. This could include support from family, some financial stability, risk tolerance, timing, and a pinch of good fortune in whatever shape. Being a full time author could have as easily happened for them if they self-published the book or started a blog or operated a non-profit for writers in their community. But I’m not denigrating that they worked incredibly hard and that they have been and are doing what they set out to do—we just need more transparency.

To say that being underpaid and to glorify poverty as a “natural part” of being a new writer is to normalize the justification that these things will open future opportunities is DANGEROUS and actively hurtful. And it’s just a massive shit to take on people who don’t choose to dip their toes into poverty. At the end of the day, one of my biggest concerns is the fact that essays such as these cloud the judgment of young authors who are contemplating their own path into the world of writing and trying to figure out how to build their own career as a writer and/or academic/researcher.

It made new writers gaslight themselves into thinking that maybe they should sell their work to a publisher for pennies. It made them think that yes it is okay for me to sell my work to a publisher who is literally using me for capital gain. It is okay for them to use me and my work because that’s what established authors say is normal. IT IS NOT. Don’t entertain thoughts like; I can let them use me and my work, I am okay with them paying me next to nothing, and I am going to do all of this with a smile on my face because well that’s just how things are.

THE TAKEAWAY

Published writers, journalists, poets, academics, professors, please stop spreading this irresponsible and malicious rhetoric and instead start calling out your colleagues who are spreading this dangerous and false narrative. Start saying out loud that it is NOT okay and it is NOT an expectation that graduate students, new writers, adjunct and new faculty, and new artists are exploited for their labor. You can value artists, you can value people! It is okay!

New writers, journalists, poets, academics, professors, don’t let such stories make you question what you know is wrong. Don’t sell your works and work for next to nothing.

We as a community of writers need to remind these systems that they RELY ON US! They rely on our work and our works. Remember even though traditional institutions such as publishing and academia have a long and established history of building career paths built on exploitative processes, YOU HAVE A CHOICE and can decide to NOT PARTICIPATE. Seriously, you don’t have to participate. You can become a writer, instructor, researcher, journalist in so many other ways. And these are the stories we actually need to be writing and reading about. We need alternative paths to success. We need conversations and community around writing.

I know why traditionally publishers authors are afraid to speak up because they are directly benefiting from these broken systems, but now more than ever you need to put the needs of others before your own. Advocate for change. Be the voice of reason behind those closed doors. Openly question the practices you see or talk about the experiences you yourself had. Don’t continue to perpetuate broken systems.

Just remember, publishers and academia don’t need defending, they need dismantling. They need equity.

damn, so much here I wish I could highlight.

Excellently put. There's a problem in publishing, and we have to keep pushing for better practices instead of merely accepting pennies for years and years and years of work.